In contemporary Tokyo, delicate hand dyeing “Tokyo Somekomon” is definitely handed over.

Komonzome by hand dyeing.

Hirose Senkojo, upholding the traditional techniques.

A silk Kimono, that looks unpatterned at a glance. But taking a closer look, you will find extremely detailed patterns progressibely located and delicate beauty is engrained there. Tokyo Some-Komon (Edo Komon) has developed out of patterns of a formal dress called Kamishimo featured with fine patterns dyed in single color for Samurai in Edo Period. In 1952, Cultural Properties Protection Committee (Agency for Cultural Affairs today) recognized Kosuke Komiya for his Komon-zome expertise and appointed him an Important Intangible Cultural Heritage. The technique was then named Tokyo Some-Komon to distinguish from the other types of Komon-zome.

Hirose Senkojo we visited was founded in 1918. It is a factory consistently held up its traditional culture for more than 90 years. The person we interviewed was Yuichi Hirose, the 4th generation of Hirose Senkojo and has a background of being appointed as a major candidate player of wind surfing for The Olympics. His father Kazunari Hirose, named as a Traditional Craftsman, who actively works in a variety of field such as dyeing Kimono for Kabuki actors Shoroku Onoe and Nizaemon Kataoka. Hirose Senkojo still maintains its position of staying with traditional hand dyeing (Tetsuke) while more and more factories go for machined dyeing. In the workplace called Itaba, cool air was floating and filled with smell of dye. Standing next to a Hariita in length of 7 meters made of fir tree covered with a white cloth, Yuichi puts resist paste and performs stenciling (Katatsuke). Looking up the ceiling, we found a lot of Hariita hung, that looked being used throughout decades. Techniques to produce Tokyo Komon-zone, date back to Muromachi Period, is certainly upheld even today.

Template making, stenciling, and dyeing. A consecutive work realizes prismatic aspect.

As it is said “Without having skilled template engraver, Edo Komon will become destroyed”, Edo Komon and Ise templates are closely linked together. Ise templates, used not only for Edo Komon but also for dyeing process of Kata Yuzen for example, are made with layered Mino paper with sour persimmon paste put in between. Shiroko of Suzuka City, Mie Prefecture is a major place of the manufacturing, and craftsmen work out the sophisticated patterns – called a micro space – by using carving knives designed for it.

We were allowed to step in their template storage room. In the floor space of around 4.5 tatami mats, under naked light bulbs, we found old tempates stacked up closely together. “I think we have more than 4,000 different old and new templates, at least right here. It is not too much to say this place is the heart of us. Some of these were done by Living National Treasures indeed.” Yuichi explains. These templates, in that the beauty of patterns are packed together and are recognized as the soul of Edo Komon, will be handed over generation after generation.

Well, upon stenciling finished, Yuichi started to perform “Shigoki” process that s color starch made with melted dye is put on a white cloth. “Before doing Shigoki, I perform color matching, remove impurities, and get the color starch strained through a bleached cotton cloth in order to make it finer.”. On a white cloth with handles, he puts color starch, then sprinkle sawdust on top evenly. This process is in order not to make the folded cloth stuck together by color starch when put into a steaming chamber. Having steamed at 90 degrees C for about 30 minutes in a chamber, the color is permanently set and the cloth is washed in a water tank. The whole process ends with drying in the sun. “Texture of color appears differently upon weather and humidity. Always I can’t wait for finish of dyeing but I am always anxious also.”. Going through such a variety of processes, Edo Komon becomes finished. By tracing techniques unchanged from old days on a consistent manner, tradition is handed over to the next generations.

Tokyo Some Komon, The first woman of Traditional Craftsman

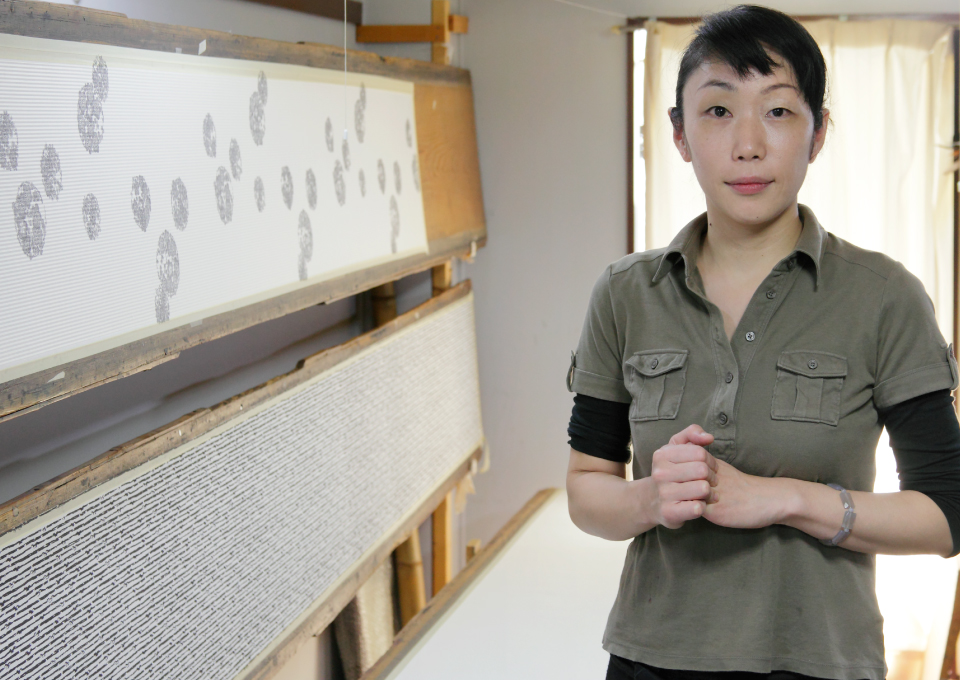

Emika Iwashita

In an apartment based in a downtown of Tokyo where number of old small factories stand side by side, we found her atelier. Having all the partitions removed away, a woman silently works on a board in length as long as 7 meters put on the floor. She is Emika Iwashita, the first woman recognized as a Traditional Craftsman in 2007.

“I have already been familialized with Kimono since childhood because my relatives were running a Kimono shop.”, Iwashita explains. Being fascinated with Edo Komon and graduating a textile course of an art college, and after working for a certain period at a dyeing factory based in Shinjuku, Tokyo despite opposition from her family, she became an independent craftsman. Now she has her own brand “Sui Rin Ka” and releases a lot of works.

“All here at this Itaba (workplace) are what I have done by myself. Lightings were purchased at a do-it-yourself store, and I used a crane to bring a board weighing 40kg into here. All were tough work though :).”

Iwashita, who says used be a girl really loved Kimono. She explains that she became aspired to being a producer of such beautiful things because of being impressed with her uncle’s words “Kimono is a painting for people to put on.”.

Iwashita performs transferring patterns of tempate to white cloth by carefully sweeping a worn paddle, while keeping the patterns of template aligned with the corresponding star marks. Although she had got sick from repeating the process in a kneeling position, she had never given up her career in traditional art.

“Edo Komon has long been positioned a world of men. So my idea is, from a women’s viewpoint, to keep offering something more fashionable and being more casually acceptable.”.

Time changes, and lack of successors is coming up as an issue around Edo Komon field. Despite the fact, there are such people who are fascinated with the beauty transcended the time, uphold the techniques silently and consistently even in a big city.

Tokyo Somekomon(Edo Komon)_Dyeing craftsmanTokyo Somekomon(Edo Komon)_Dyeing craftsman